A movie for every day of the year – a good one

25 March

The founding of Venice, AD421

On this day in the year AD421, Venice was founded. Sited on 118 islands in a lagoon between the mouths of the rivers Po and Piave, Venice derives its name from the Veneti people who lived in the region in the 10th century BC, though the people who actually founded the city were more likely refugees fleeing the Germanic and Hun invaders who were flooding into Italy as the Roman empire fell apart. Today is traditionally taken as the day of the city’s founding because on this day in 421 the church of San Giacomo was dedicated. It still stands, though it was substantially rebuilt by order of the doge Marino Grimani after a fire destroyed much of the area.

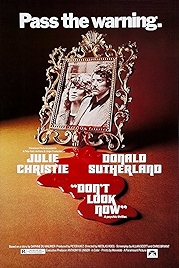

Don’t Look Now (1973, dir: Nicolas Roeg)

It’s often remembered as the film in which Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie have sex for real for the camera, though that story smacks of brilliant PR rather than Perez Hilton-style tittle-tattle. But Don’t Look Now’s most talked about scene is important for another, more structural reason. It’s the way that in the editing of the scene the action keeps cutting between the present and the future. The story of John and Laura Baxter, a young married couple whose daughter has died in a drowning accident, Don’t Look Now has already shifted location from misty England to Venice where, as some sort of sublime joke, the Baxters are meant to be recovering from their loss in the world’s most watery city. He’s restoring a cathedral as part of his work; she’s quietly going nuts.

And it’s in the cutting that Roeg and editor Graeme Clifford signal Laura’s disintegration, the way they collage together images of the here and now with suggestions of what’s to come, or of this world of solid mass with an alternative world which is just out of reach. Enter two sisters, one of whom can “see” the Baxters’ dead daughter. Enter a priest, too worldly by half. Exit Laura, to sort out some problem back home. And here, after much suggestion and foreshadowing, the film goes into its most famous sequence, as the entirely rational John starts chasing around the spookily empty Venice after a hooded figure in a red coat just like the one his daughter was wearing the day she died. There’s nothing overtly “horror” about this film; it doesn’t do “boo” scares or feature mad axe-wielding psychopaths. It works on the senses in a different way, insidiously, by suggestion, the film built shot by shot like some baroque fugue – themes are stated, restated with embellishment, echoed, reversed, until (ta daa) we reach the final reveal. Plot junkies won’t like the ending. It’s too abrupt, seems like too sudden a change of direction. Yet as Laura glides away with the two mysterious sisters on boat across the water – allusion to Greek mythology surely deliberate – surely it’s the best ending possible for a film that’s been about the boundary between the solid and the ethereal.

Why Watch?

- Nicolas Roeg’s best film

- Probably the most subtle gothic horror ever made

- Perfect Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie

- A masterclass in cinematography and editing

Don’t Look Now – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014