A movie for every day of the year – a good one

18 April

Miklós Rózsa born, 1907

On this day in 1907, the celebrated and prolific film composer Miklós Rózsa was born, in Budapest, Hungary. His mother was a pianist and his father was a wealthy industrialist. Young Miklós was performing in public and composing at the age of eight. After studying in Leipzig, Germany, he moved to London, where fellow Hungarian, the producer Alexander Korda gave him his first film to score, 1937’s Knight without Armour. Rózsa went to Hollywood with Korda to work on The Thief of Bagdad, then went on to work on several Billy Wilder films, including Five Graves to Cairo and Double Indemnity. In 1945 three of his scores (for Spellbound, The Lost Weekend and A Song to Remember) were nominated for an Oscar (Spellbound won). Among the films that Rózsa then went on to score were The Killers, The Naked City and Ben-Hur, the last winning him his third Oscar. He continued working on film scores into the 1980s – Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid was his last – his tally of completed works by then standing at over 90. He was also a prolific writer of concert works.

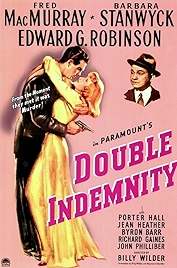

Double Indemnity (1944, dir: Billy Wilder)

No matter how resistant you are to old films, films in black and white, the arch histrionics of Barbara Stanwyck or Fred MacMurray’s big chump persona, within five minutes of the beginning of Double Indemnity you will be hooked. It is close to being the perfect film, devastating in its logic, with a script that is as hard-boiled as it is playful. The key scene comes immediately after the opening credits, when insurance salesman Walter Neff (MacMurray) tries to sell a policy to feisty bright dame Phyllis Dietrichson (Stanwyck). Immediately we know where we are and what’s going on – though he doesn’t know it, Neff is the anti Philip Marlowe, a wiseguy who isn’t quite wise enough. He’s got the hat and the patter and he’s very sure of himself. He’s his company’s top salesman and has earned the right to swagger. And as we sit back and watch, there he is being absolutely and exquisitely worked over by a woman he can’t believe is trading flirtations with him, a hot babe who wears an ankle chain – woo hoo.

By the end of the scene Walter – how that name sounds when Stanwyck purrs it – is trussed up tighter than a capon, and is on the way to agreeing to sell Mrs Dietrichson’s husband an expensive life policy before murdering him. After that they’ll cash in and start a new life together. This last bit doesn’t seem even faintly likely to happen, given the slipperiness of her and the over-eagerness of him – and the cinema code of the time would never let such a thing happen either – so what Neff and Dietrichson are doing and what we’re watching are two entirely different things. We know it, Wilder knows, we know Wilder knows we know it. And so on. Only Neff and Dietrichson seem oblivious. It’s a slo-mo car crash of a film noir – one of the first of the genre – with director Billy Wilder constantly teasing, holding off the awful moment of reckoning. Enter Edward G Robinson as Walter Neff’s boss Barton Keyes, a cigar-smoking pernickety investigator who, from his slightly stagey delivery and bookish persona, seems to be operating in a different film. He’s the one whose simple questions, adherence to protocol and actuarial tables starts to uncover their scheme – what potential suicide, he asks, jumps off a train travelling at 15 miles per hour to kill himself? Or was he perhaps helped to jump?

And from that observation onwards Walter and Phyllis are done for. The film is about process – how Neff and Dietrichson first tie each other into murderous knots, and then how Keyes unpicks them. Raymond Chandler rewrote James M Cain’s pitiless story, adding all the juicy to and fro between Neff and Dietrichson (Phyllis: “I think you’re rotten”. Walter: “I think you’re swell – as long as I’m not your husband”.) and even if it wasn’t at all satisfying in terms of cast and plot, the dialogue alone would make it double-worth it.

Why Watch?

- One of the first and best film noirs

- Raymond Chandler’s dialogue

- Miklós Rózsa’s score

- Cinematography by John F Seitz (The Lost Weekend, Sunset Boulevard)

Double Indemnity – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014