A movie for every day of the year – a good one

2 June

The sack of Rome, AD455

On this day in the 455th year of the Christian or Common Era, Rome was sacked. Actually, this is a touch ambiguous, because Rome had already been pillaged twice before, in 390BC by the Gauls fighting the Roman in the Battle of the Allia; and in AD410, in the attack of the Visigoths led by Alaric. In AD455 it was the Vandal king Genseric who marched on Rome, claiming a peace treaty between himself and Emperor Valentinian III had been violated when Emperor Petronius Maximus had usurped Valentinian and seized the throne. Out of deference to Pope Leo I, the Christian Genseric kept the violence and looting to a minimum. Genseric threw open the gates of Rome, allowing beaten Maximus and his men to flee, then set about a systematic plunder of Rome’s wealth, which continued for 14 days. Much treasure was taken and many people were eventually sold into slavery in the markets of Carthage (North Africa), a Vandal stronghold. Genseric withdrew to Carthage, taking the wife and children of the deposed Emperor Valentinian III with him. The word vandalism has had a cultural significance since.

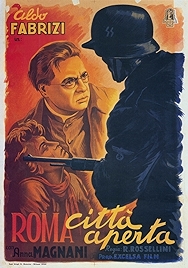

Rome, Open City (1945, dir: Roberto Rossellini)

Co-written in a week with his friends Sergio Amidei and an unknown Federico Fellini, Rossellini’s Rome, Open City was made in the teeth of adversity. Italy was in the final days of the Second World War. Its leader, Mussolini, had fled and was about to be taken out and hanged from a lamp post.

Rossellini, meanwhile, was making a film that marked a kind of Year Zero (a title he’d later use in another film, Germany Year Zero) of film-making. Looked at today it can be hard to see what the fuss was about – the neo-realist style, shooting out on the streets, using non-actors in key roles, that’s becomes absolutely standard. Back then it really wasn’t – films were made in studios, with heavy cameras, lights and teams of backroom technicians oiling the wheels.

Yet, even without that initial shock of the new, this film works. Some of that is down to the fact that Rossellini is shooting in a city that has just been liberated by the Americans, ravaged, bombed out, its people shaken and hungry – there’s a definite documentary aspect. Then there’s Anna Magnani, a cabaret star on her way to being the same in film, as the fiancée of a Resistance fighter hiding from the Gestapo and later betrayed by someone in the organisation.

Its most famous shot is of Magnani running down the road after a truck as the Nazis take her man away. Shot being the operative word in that sentence, the first of a series of dramatic shocks that spike the film. Can you imagine the power of this film, conceived while the jackboots were still on the streets, made on the hoof, guerrilla style, necessity forcing its stylistic decisions, then shown to a populace who had been subject to the “open city” of the Nazis (it’s a German way of saying “game over”) only a few months before, and unstinting in its depiction of the brutality of the occupiers?

Some aspects of the film have dated now – the broad-brush Nazis were absolutely necessary then but not so much now; homosexuality is treated in the sort of way that might make a modern viewer flinch. Even so, it is the first film of the glorious renaissance of Italian movies after the war, this and Bicycle Thieves being the landmarks of the neorealist movement. Jean-Luc Godard, when asked about the origins of the French New Wave 20 years later, declared “All roads lead to Rome, Open City.” Rossellini would never make a film as powerful again.

Why Watch?

- An epoch changing film

- Rossellini’s best film

- An early sight of a future legend – Fellini

- Anna Magnani’s starmaking performance

Rome, Open City – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014