A movie for every day of the year – a good one

29 May

The Rite of Spring premieres, 1913

On this day in 1913, Russian composer Igor Stravinsky’s orchestral ballet The Rite of Spring premiered at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris, France, as part of a season of performances by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The reaction to it was instant and violent, with laughter greeting the opening bars of the introduction. This grew into a “terrific uproar”, according to Stravinsky’s autobiography. He also detailed how he watched from the wings as the choreographer, Nijinsky, was forced to shout out the step numbers to the dancers, who couldn’t hear the music. People in the audience began throwing things but the orchestra played on, managing to make themselves heard, though a commotion continued through the entire performance. Whether the disturbance was aimed at the rhythmic music or the often pagan movements of the dancers, or whether it was more the outbreak of hostilities between the more conservative and bohemian elements in the audience remains a moot point. The next day in the papers, the critics were split, Le Figaro calling The Rite of Spring “puerile barbarity” while the theatrical magazine Comoedia described it as superb. Others again thought the music wonderful and the dancing appalling. Stravinsky’s autobiography records that after the performance Stravinsky, Nijinsky and Diaghilev went for a celebratory dinner with Jean Cocteau.

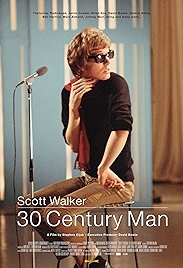

Scott Walker: 30 Century Man (2006, dir: Stephen Kijak)

The British-based American expatriate Scott Walker was a pop idol in the 1960s. Thanks to his good looks and baritone voice he had a string of hits with the Walker Brothers – named after him, though his real surname is in fact Engel. Then he went solo, making a number of critically hailed and artistically influential solo albums inspired to large extent by the chanson tradition of the likes of Jacques Brel. These were followed by a series of increasingly minimal and doomy avant garde albums. Both the Brel-flavoured and avant garde music made an indelible impression on David Bowie in the 1970s, who borrowed much of Walker’s angularity and swagger.

When Stephen Kijak caught up with him for the making of this documentary, Walker had just released his first proper album, The Drift, for over ten years. Whether you buy into the idea of Walker as towering avant garde genius or not, there is something to see here. If you do it’s the sight of a man often described as a recluse being surprisingly open, honest, chatty and happy – human. If you don’t, then it’s his unusual attitude – an artist who makes absolutely no claims for the value of what he does. According to Walker, he does what he does because he enjoys doing it, that’s all.

This unexpected and simple credo is one of the most refreshing things about a film that looked, from the title, like it was going to be all hagiography. There’s the personal stuff too, Walker’s fairly frank admission that “the imbibing”, as he describes the years of drinking too much, got in the way of his work. And some backstory – the early years of pop adulation, the attempts to keep the Walker Brothers going, their eventual demise in the 1970s after a botched comeback, the infighting.

Let’s not get carried away though, there are plenty of what you might call the usual suspects – Johnny Marr, Damon Albarn, Bowie (who is named as executive producer), Johnny Greenwood, Brian Eno – bending the knee in front of one of avant garde pop’s totemic figures, revered in Britain, largely ignored back home. Scattered between the we’re-not-worthies are insights into the way Walker works. These are fascinating too: the way he buries the melodic line of a song so the musicians and even the producer can’t find it, for instance. Or punches a hanging animal carcase to get the right percussive sound. Stravinsky, Ligetti and Gorecki can all be heard in the resulting opus – pop musicians are often not quite as “avant” as they are billed – but Walker undoubtedly has had an influence on how popular music is written and consumed.

For his part, Kijak clearly knows a thing or two about working in the language of film – the pacing of his shots and his editing are deliberately intended to create a hypnotic effect. This too is unusual in a documentary about a musician, which tend to take the backstage/onstage route. Do we in the end get to know much more about this man, still looking boyish as he goes into his seventh decade? Not particularly. But we do get to know a bit more about his music, and in any film about any artist what you really is to learn about the work, isn’t it?

Why Watch?

- A hypnotically constructed film

- Walker’s engaging personality

- The talking head endorsements

- The strange, ethereal music

Scott Walker: 30 Century Man – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014