A movie for every day of the year – a good one

30 June

Dave Van Ronk born, 1936

On this day in 1936, one of the great nearly men of popular music was born, in Brooklyn, New York, USA, into a Catholic family who identified as Irish. Dave Van Ronk was singing in a barbershop quartet by the age of 13 but left school early to play music, hang around in Manhattan and, eventually, ship out with the Merchant Marine. He played jazz before straying upon blues, and built up a small following as one of the few white men working in the genre. And from there broadened out into folk. As the folk revival of the late 1950s gathered pace, Dave almost became part of a folk trio, which would have been called Peter, Dave and Mary. But the gig instead went to Noel Paul Stookey, and so Peter, Paul and Mary it was. Instead Dave wrote songs and sang in Greenwich Village; he became the figurehead of the scene, his syncopated finger-picking style and big bearish personality gaining him many admirers. Dave “was king of the street, he reigned supreme” as Bob Dylan later put it. However, in spite of 20 albums and five decades of performing, few people outside of the aficionados ever got to hear of Dave Van Ronk. This was partly because he wouldn’t fly, couldn’t drive, disliked leaving Greenwich Village. But it was also simple bad luck – he did a beautiful, crack-voiced version of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now”, which should have been a hit, except that Judy Collins beat him to it. And then, suddenly, the folk moment was over and the Tom Paxtons and Ralph McTells and Dave Van Ronks had to content themselves with driving on the back roads of success. Well at least he had talent, and did it his way.

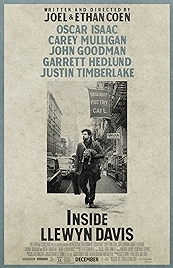

Inside Llewyn Davis (2013, dir: Ethan Coen, Joel Coen)

The Coen brothers borrow the title of the 1964 album Inside Dave Van Ronk to tell the story of another nearly man, the fictional Llewyn Davis. Davis is not Van Ronk, and it’s pointless drawing comparisons between the two. Because Llewyn Davis is so clearly a Coen man. In other words, someone who’s doing what he thinks is his best but it isn’t really working for him. “Everything you touch turns to shit. Like King Midas’s idiot brother,” says Davis’s ex squeeze (Carey Mulligan, all over that Joan Baez look and attitude). We’re in Greenwich Village, early 1960s, folk music riding high, the clubs full of nice middle class kids in chunky sweaters, either on the stage or in the audience, while out in the wider world of music Llewyn Davis is trying to make a go of it.

The cat. We have to mention the cat, which Davis accidentally lets out of the apartment of the people he’s staying at, then chases down the road, then catches, then takes home to look after for a few days, because he can’t get back into the apartment now that the door has clicked shut behind him. And by “home” he means the couch of another long-suffering “friend”.

The strength of this film comes from its highly charged individual scenes – Davis abusing the hospitality of the Upper East Siders who have been bending over backwards to help the struggling artist; Davis being refused an advance by his ancient agent; on the road with a derisive heroin-addicted jazzman (John Goodman, nice); being told at the famous Gate of Horn club that he hasn’t got what it takes (and after singing his heart out too). And on it goes, heartbreak in instalments, to a lovely soundtrack, in venues that look lifted straight off the cover of Bob Dylan’s Freewheelin’ album.

The Coens have introduced us to Davis just as he’s obviously run out of time, credit at the goodwill bank of his various friends, couches to kip on. Something has to give. The songs Oscar Isaac tenderly sings are Dave Van Ronk’s. And they’re beautiful songs, though not quite “hooky” enough to make it. Davis isn’t “hooky” enough either, is chasing fame (or even just a living) the way he’s chasing the cat – elusive, indifferent – which actually turns out to be the wrong cat entirely.

As to whether the Coens are offering an explanation for Davis’s status as a nearly man, I’m not sure they are. There are suggestions that maybe Davis wants the prize for the wrong reason – money, rather than art – but only the vaguest hints. Instead the Coens seem intent on building a sustained mood piece in a minor key, highly polished, terribly sad. They are unusually fair to the music, make no snide digs at well brought up Americans singing in odd approximations of British folk accents, or of white kids who want to be black. And at the end, as Davis packs up his guitar having sung yet another night at the club he’s inhabited like a bad smell, and as he wanders outside into the back alley, the next act is announced. It’s Bob Dylan, we hear. But we don’t see. Success is not what Inside Llewyn Davis is about.

Why Watch?

- Oscar Isaac’s haunted performance

- The music, including Dave Van Ronk’s songs

- So many great performances – including Carey Mulligan, F Murray Abraham,

- Bruno Delbonnel’s era-evoking cinematography

Inside Llewyn Davis – Watch it now at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014