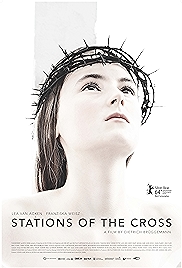

A powerful and formally austere German drama that does exactly what it says on the label, Stations of the Cross charts the sad journey of one vivacious Catholic girl to an early grave in 14 grim instalments which echo those of Jesus Christ on the way to Calvary.

The Catholics also knew the Stations as the Via Dolorosa, or the Way of Sorrows, the Latin name doubly appropriate here since devout, cusping-on-puberty Maria (a remarkable Lea Van Acken) is being prepared for her confirmation by the charismatic Father Weber (Florian Stetter), a priest in a breakaway part of the Catholic Church that still uses Latin. This branch of the Church is also positively medieval in its theological outlook. The world is sinful, abnegation is a virtue, things denied down here count for something up there, the charismatic and creepy Weber making something of the fact that he’s not going to have that bar of chocolate, not going to listen to “that beautiful concert on the radio”. Things are similar at home, Maria’s mother a bright-eyed zealot, father cowering in near-silence while Maria’s four-year-old brother Johannes hasn’t spoken since birth. Is it autism? Is Johannes touched by God? Traumatised?

But Satan comes clothed in a variety of guises. Whether it’s the family’s French au pair Bernadette, a Cafeteria Catholic – pick what you want, leave the rest – or Christian (Moritz Knapp) at school, who is keen to get Maria to sing in his church choir, where as well as “lots of Bach chorales” they sing soul and gospel. He may be keen to get at more of Maria than her vocal cords, and for her part Maria admits in the confessional to the smooth, wheedling Father Weber that she might have dreamt about Christian putting his arm around her.

The poor chaste lamb needs it. She’s pale, thin, wears hardly any clothes when it’s clearly cold out. And after mother hears of the “gospel… soul… jazz…whatever”, sinful devil’s music, things erupt and what in most families would be a rites-of-passage row about new feelings for members of the opposite sex becomes for the mother a crusade against a new darkness, for the daughter a new opportunity to demonstrate her self-denial (which might well be a sinful expression of pride, she confides to Bernadette).

A powerful story, then, especially as it progresses from this point, but it’s the manner of its telling that has been winning the film awards at festivals all over the world. Director Dietrich Brüggemann and co-writer/sister Anna Brüggemann plot Maria’s story in exact parallel with Jesus’s journey to Calvary, each of the film’s 14 chapters being marked as a different “station of the cross” – from 1. Jesus is condemned to death, to 14. Jesus is laid in his tomb. If that’s spoilerish, take comfort from the fact that it won’t be to anyone familiar with Christianity. Given the title of the film, once we’ve seen that first intertitle, there’s really only one way this can go. Though the Brüggemanns do have a little fun on the way. Stage 5 (Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus to the cross) and stage 6 (Veronica wipes the face of Jesus), as well as being intensely powerful individual scenes, both work at 180° to what their chapter headings suggest.

And festival juries have also been falling over themselves with admiration for the Brüggemanns’ shooting style, each station a single flatly lit locked-shot, inside which there is some movement, though not much.

In the tradition of “from the inside out” films such as Hans-Christian Schmid’s 2006 German exorcism shocker, Requiem, rather than more conventional “outside in” horrors such as Pascal Laugier’s 2008 French/Canadian gorno Martyrs, it’s the movie equivalent of the sort of static stations of the cross you might find in almost any church. Except here a girl called Maria is taking the part of Jesus, and men are for the most part either passive (Maria’s father) or pulsing with dangerous power (Father Weber). Someone is turning the tables on gender relations in Christianity, it would appear. But Stations of the Cross is so muted in its modus operandi that it can be read a number of ways. As an argument against any sort of fundamentalism – religious or, this being Germany, political. As a starting point for a discussion about multiculturalism, and how we accommodate belief systems who don’t want to be accommodated. Or it can even be taken at face value – if you ignore all of the Brüggemanns’ inducements not to – as the story of a pious girl in a secular world who becomes, through rejection of the blandishments of the devil, a saint.

Stations of the Cross – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014