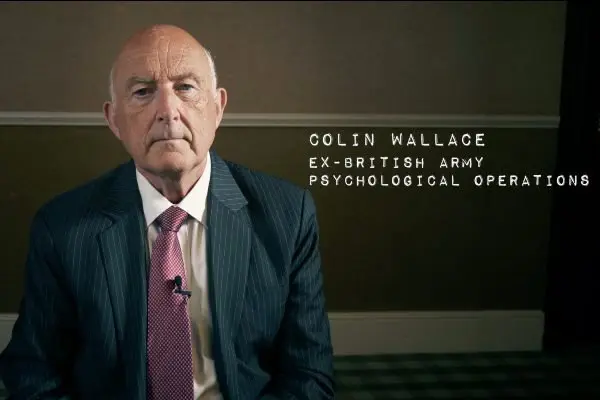

James Stewart? Doris Day? Alfred Hitchcock? No. Instead meet Colin Wallace, a retired real-life spook who got heavily involved in the UK government’s undercover operations in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, blew the whistle when his paymasters started asking him to start smearing democratically elected politicians, then wound up in jail on a ten-year stretch on a confected charge of manslaughter. Strangely, or perhaps it’s not strange at all, it’s a tale from recent history with an urgent contemporary relevance.

Michael Oswald’s documentaries to date have all sought to pull back the veil on the hidden workings of the world. Finance was the focus in 97% Owned, Princes of the Yen and The Spider’s Web but in The Man Who Knew Too Much Oswald concentrates on the shady world of everyday espionage and government overreach, the point where the elected administration of the day starts to fancy itself as the state – its “l’état c’est moi” moment.

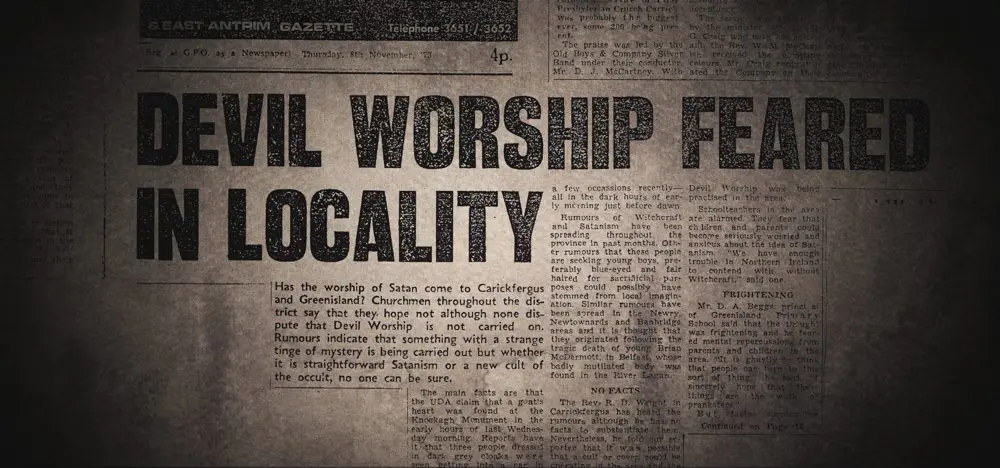

Softly spoken Wallace talks us through his remarkable story – as the Troubles got underway, the Northern Ireland native was drafted in to the UK government’s psy ops team because of his local knowledge. From the early 1970s onwards he started using friendly journalists to drip-feed stories into the press, stories designed to destabilise the terrorists’ narrative. Some of these were lightweight, some bizarre – the glut of newspaper articles on satanism in the region were all Wallace, for example – others more routinely linked terrorism to the Vatican or the Soviet Union, whoever happened to be plausible. Disinformation, misinformation, anything that muddied the water.

Good at his job, Wallace’s technique for getting a story up and running was one that’s even more prevalent today in the world of all-pervasive social media. He would write pseudonymous letters to tiny local papers raising the issue of, say, satanism, then use those same letters as “evidence” of what was being talked about at a local level to punt the story further up the news chain. The entirely synthetic story would get legs.

Wallace’s story gets darker from here as it forks in two different directions. One involves a Loyalist organisation called Tara, headed by William McGrath, who operated a paedophile ring out of the Kincora Boys Home. The Northern Ireland authorities knew what was going on but were reluctant to hand a propaganda victory to the Republicans and so kept a lid on the organised abuse allegedly involving high-level officials, a scandal that continues to resonate.

The other is Wallace’s involvement with what became known as Clockwork Orange, an attempt in the mid-1970s by rogue elements inside the UK security services to destabilise the elected government by smearing politicians, all the way up to the prime minister.

A patriot but also clearly a believer in the rule of law, Wallace had not signed up to protect paedophiles nor to help facilitate a right-wing coup and so started to speak out. For his efforts he was fired and eventually wound up in jail, convicted on a trumped-up charge of having killed the husband of a woman he was said to be having an affair with.

He served six years before being released. More years went by before his conviction was overturned.

It’s a murky tale, at its sharpest in Wallace’s early days. The focus blurs as the story shifts to the boys home and the smearing of UK politicians. As the voluble Wallace becomes cagier (the chill winds of the Official Secrets Act), Oswald’s array of journalists and historians are called on increasingly to plug the gaps with informed speculation.

Wallace might be the focus of this film, but its actual subject isn’t him but the UK state. Nor is it even really the UK state, but elements within it acting on its behalf. These people remain unidentified, though Wallace knows many of the names – as recently as February 2019 Wallace was urging the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland to answer some of the many unanswered questions. Silence.

Knowledgeable though Oswald’s witnesses are, the absence of key witnesses means the whole story cannot be told here. But a film about fake news, election tampering, a high-level paedophile conspiracy and the deep state, how much more contemporary relevance do you want?

Click here for screenings of The Man Who Knew Too Much

© Steve Morrissey 2020